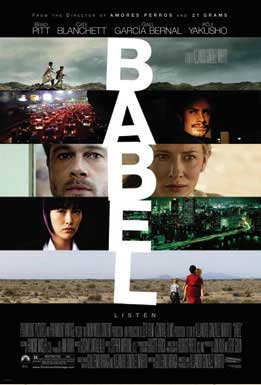

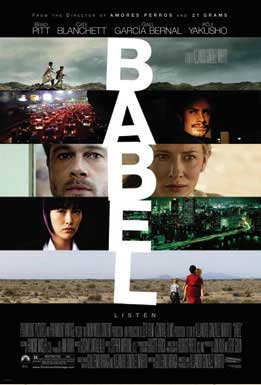

Babel, directed by Alejandro González Iñárritu(for which he won the Best Director award at Cannes) and written by Guillermo Arriaga, has gotten press for the controversies surrounding the director and the screenwriter. But the focus should be on the film itself. The movie that completes the trilogy started by Amores Perros and 21 Grams, Babel intercuts between four interconnected stories, often jumping time periods.

Babel, directed by Alejandro González Iñárritu(for which he won the Best Director award at Cannes) and written by Guillermo Arriaga, has gotten press for the controversies surrounding the director and the screenwriter. But the focus should be on the film itself. The movie that completes the trilogy started by Amores Perros and 21 Grams, Babel intercuts between four interconnected stories, often jumping time periods.

It is riveting. And bloody stressful. Once it sets the tone that nothing is going to go well, I sat the edge of my seat knowing bad shit was going to happen at every turn.

Warning – some spoilers ahead

At the core, Babel is a story about communication and the challenges we face due to different languages, different perspectives, in-built biases and different expectations. Richard (Brad Pitt) and Susan (Cate Blanchett) are on a vacation in Morocco. At the same time, two young goatherds are given a rifle by their father to keep the jackals away. Hmm, let�s see — two young boys have a gun. They have to test the gun. The tourists are in a bus. The bus passes by under the hill the boys are on. Of course, bad shit happens.

An injured Susan is taken to the closest town with a doctor (a veterinarian) as they wait for the US embassy to extricate them. At the same time, the boys are forced to deal with the consequences of their actions (read – bad stuff is going to happen).

In parallel we see the story of a Mexican nanny, Amelia (Adriana Barraza), who takes wonderful care of Mike (Nathan Gamble) and Debbie (Elle Fanning, who has the same gamin vulnerability as her sister Dakota). Amelia is desperate to go to her son’s wedding, but the parents of the kids are held up as the mother has to undergo surgery. So Amelia, after exhausting all other options, decides to take the kids with her to Mexico for the wedding. Bad, bad move, as we all know.

Goddamn it. I didn’t enjoy the wedding at all since I was waiting for the inevitable bad shit to happen. Fortunately for me, the wedding passed off fine, but then of course, bad shit does happen. The kids and Amelia are stuck wandering the desert. When Amelia is finally picked up, the immigration officers refuse to believe her story, refuse believe there are kids somewhere out there and they arrest her.

Also in parallel, we see the story of Chieko (Rinko Kikuchi), a deaf-mute Japanese schoolgirl, who lives with her father. Chieko is an emotional wreck after the death of her mother and she struggles with the fact that most normal guys will not make any effort once they discover her communication challenges. She is desperate for attention, for love, for validation. The need to feel worthy gets expressed sexually as she flashes boys at a restaurant and tries to french kiss her dentist in a desperate attempt to feel wanted.

As Chieko returns home, two police detectives are waiting for her. They want to talk to her father about a hunting rifle he may have gifted to his guide in Morocco. Much later that evening, after yet another rejection, Chieko calls one of the police officers. When he visits, she strips down and begs him to make love to her. Her eventual breakdown is quite heart wrenching.

There were three scenes that stayed with me

- Richard and Susan have a difficult relationship. We don’t know why (at this point), but they are not very nice to each other. But once she gets shot, all that changes. There is a scene where Susan is in a hut in the village and she talks about dying. Then she talks about how she peed because she couldn’t hold it and that she has to pee again. Richard gets a pan, sits her up and holds the pan under her while she urinates. The intimacy of the moment, the history needed between a husband and wife to do that and emotion of what’s happened breaks down all walls and they kiss. The willingness to help another human being with one of the most private things, and the willingness to be helped, with no shame, with no disgust, with no apology happens so rarely and is perhaps one of the strongest bonding moments between a couple. It was mind-blowingly believable.

- Amelia’s relationship with the children is beautifully constructed. You can see the love they have for each other. When Amelia is arrested, she asks about the kids and officer brusquely tells her they are not her kids. In tears, she talks about how she fed them and looked after them since they were kids the officer brusquely cuts her off and threatens to deport her. Barraza did a brilliant job. I felt most sorry for her situation.

- In the final scene of the movie, Chieke is standing at the balcony, completely naked. When her father comes home, he discovers her there. He walks up to her and neither of them says anything as he hugs her and she weeps. The camera keeps drawing back from their embrace – flies backwards into Tokyo, keeping the building and Chieke and her father at the center.

The cinematography by Rodrigo Prieto was excellent. Different styles were employed for each story. Morocco was desolate, vast expanses, lots of wide angles. In the Mexico story, you could fee the heat and dust and in Tokyo, the techno-city comes to life. And the music was brilliant. Gustavo Santaolalla is to be highly commended for the guitar track that underlay the film. Exceptional.

Did I enjoy it? I guess I did. I was so damned stressed that I didn’t feel happy at any moment during the film. But I was glued to my seat, glued to the movie, praying that bad shit doesn’t happen, at least to the kiddies. Did I get my wish? You’ll have to watch the movie!

Note: This review is pre-release. I saw the film tonight (Wednesday) and it releases in the US on Friday. There was a discussion with Jon Kilik, one of the producers, before the screening. Read about it here.

Babel, directed by

Babel, directed by  Flags Of Our Fathers takes a realistic look at the events that led to the raising of the flag and lives of the men who were enshrined as heroes for cynical, marketing purposes.

Flags Of Our Fathers takes a realistic look at the events that led to the raising of the flag and lives of the men who were enshrined as heroes for cynical, marketing purposes.